In today’s wine discourse, “old vines” has almost become a quality implication that requires no explanation. It frequently appears on labels, in reviews, and in market narratives, and is often directly equated with greater concentration, deeper complexity, and even a truer expression of terroir. However, the widespread use of this association does not mean it has been sufficiently tested. Is vine age the cause of quality, or the result of quality being preserved? Does the concept of “old vines” carry the same meaning under different natural and viticultural conditions?

This article does not attempt to answer whether “old vines are better.” Instead, it treats vine age as a variable—one that must be observed, compared, and qualified within specific systems. Through three wines that differ markedly in their mechanisms of survival and ecological conditions, this article examines what old vines change within different systems, and where their influence stops being decisive.

Old Vines in three systems: Observation, not generalization

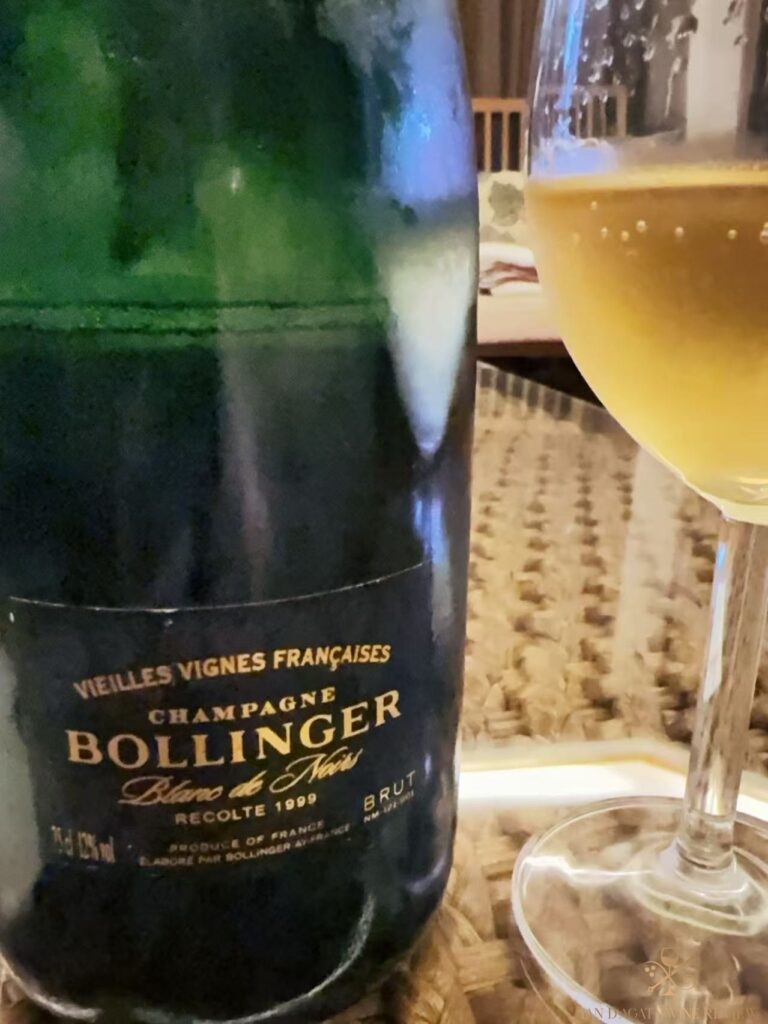

Bollinger 1999 Vieilles Vignes Françaises

Old vines as an institutionally maintained exception

The significance of Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises in discussions of old vines does not lie in the absolute number of years, but in the highly atypical nature of its survival mechanism. I recently had the 1999 and it was exceptional, so the question arises what the contribution of those old vines is really all about. In Champagne, as everywhere else, after the phylloxera crisis grafting onto American rootstocks was not a stylistic choice but a necessary condition for maintaining continuity in viticulture. Therefore, the few ungrafted vineyards from which VVF comes—mainly in Aÿ and Verzenay—cannot be seen as a natural outcome of the region’s evolution. They are better understood as historical exceptions preserved through the combined effects of specific soil conditions (a higher proportion of sandy structure reduces phylloxera viability) and long-term, systematic human maintenance.

This point is crucial: the continuation of VVF is not ecologically self-sustaining, but an institutional choice. Extremely low yields, significantly higher disease risk than conventional Champagne, and an almost non-replicable economic model mean this wine is produced only in a very small number of vintages. Under such highly controlled and non-scalable conditions, “old vines” in VVF does not constitute a transferable model; it is closer to an experimental condition that is continuously maintained.

Sensory-wise, this background has not translated into greater intensity of expression. The 1999, for example, does not rely on aromatic expansion or the accumulation of flavor layers to build complexity; what is more noteworthy is its structural behavior. The wine’s development follows a distinctly vertical path: structure becomes apparent in the mid-to-late palate, acidity serves primarily as support rather than propulsion, and the fineness of the bubbles reinforces overall tightness without creating an additional peak of tension. Persistence on the finish is driven more by the continuation of the framework and stable presence after resolution than by shifts in flavor contours.

In this context, VVF is not a sample that “proves old vines are better,” but a reference point for defining the boundaries of old vines’ influence: when the existence of old vines depends on continual maintenance rather than ecological self-sustainability, their impact is often reflected first in a change in mode of expression rather than an increase in intensity.

Tenuta delle Terre Nere 2020 Etna Rosso Prephylloxera La Vigna di Don Peppino

Old vines as an ecological norm

In sharp contrast to the singularity of VVF, pre-phylloxera old vines on the north slope of Mount Etna represent an ecological norm that still operates today. In this volcanic system, coarse soils composed of lava and volcanic ash reduce the long-term survival and spread of phylloxera at a physical level (the parasite cannot burrow in its tunnels because the sandy walls cave in on it), allowing ungrafted vines to persist systematically. Here, old vines have not been “preserved”; they have never been forced out of their biological context.

This difference makes Etna a highly explanatory sample for discussions of old vines: the existence of old vines does not rely on human protection but is supported by geological conditions themselves. The Prephylloxera wine therefore does not point to an isolated historical remnant, but reflects a long-term and stable continuity of cultivation. Within this system, vine age is no longer an exceptional state, but a background condition upon which structure can be established.

The 2020 vintage, relatively balanced and lacking extreme climatic tension, makes this background especially clear in the glass. The wine does not build presence through ripeness or vintage drama; its core lies in structural order itself: acidity shows a stable, extended linear trajectory; tannins are fine yet provide continuous support; and the pace of development is slow and even. Aromatics remain restrained, and flavor does not seek to dominate early, but gradually reveals tension in the mid-to-late palate. On the finish, persistence comes more from the integrity of the structural framework than from the piling up of flavor layers. Here, old vines do not translate into a louder “volume,” but function more like a structural stabilizer—reducing uncertainty of expression and helping maintain proportion and rhythm in the absence of external pressure.

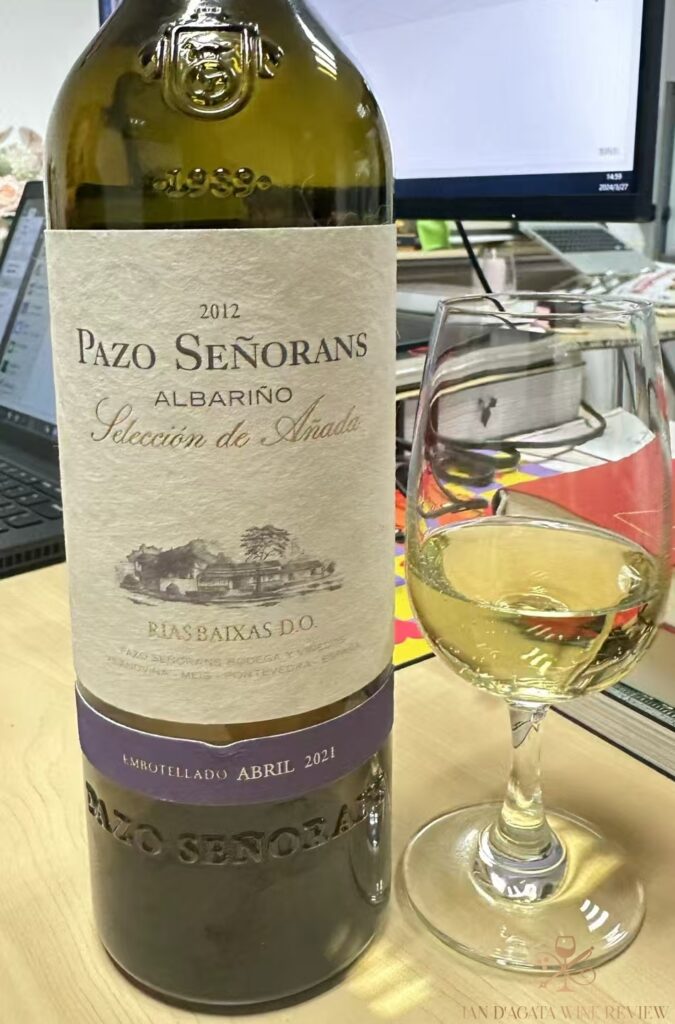

Pazo de Señorans 2012 Albariño Selección de Añada Rias Baias

Old Vines as Structural Durability Under Local Conditions

In Rías Baixas, old-vine Albariño does not exist as a systemic norm, and is better understood as a local condition dependent on specific site factors. The Val do Salnés area is dominated by granite bedrock; in some parcels, long weathering has formed soils with strong drainage and relatively coarse texture. Such conditions can, to some extent, reduce the survival and spread efficiency of phylloxera, allowing some vines to persist over the long term.

Selección de Añada is not simply a vintage selection. It is a sample chosen from mature old-vine parcels with long-term structural potential, and tested for stability in the time dimension through extended lees contact and bottle ageing. This makes the wine closer to an observation window than a stylistic declaration.

Structurally, the 2012 vintage is particularly instructive. The wine does not establish presence through aromatic intensity; its core is a linear and sustained high-acid framework. Acidity sets the direction at entry and continues to pull the wine forward through the mid-to-late palate. The texture shows a degree of oiliness, providing width and buffering for the taut acidic structure, allowing proportion to be maintained between tension and expansion. On the finish, persistence is driven primarily by the layering of mineral tension and salinity rather than by the accumulation of flavor layers. Even after extended bottle evolution, the wine still shows no obvious oxidative traces. This state is better understood as an expression of structural durability rather than an extension of a single flavor profile. In this context, the role of old vines is not to amplify expression, but to provide sufficient material basis for a high-acid system to withstand the test of time.

Selection Mechanisms and the Boundaries of Old Vines’ Influence

Placing the three systems discussed above side by side does not lead to a unified “old-vine style.” Rather, they reveal the different roles that old vines play within different systems: in Champagne, old vines are a historically exceptional case maintained through institutional means; in Etna, old vines form part of the ecological background that allows the system to continue; in Rías Baixas, old vines constitute one of the conditions for structural durability in high-acid white wines. These differences alone indicate that vine age cannot be interpreted independently of the system in which it exists.

In theory, vine age itself does not constitute a guarantee of quality. Yet in practice, old vines frequently appear in the context of high-quality wines. Explaining this phenomenon solely through biological advantage is clearly insufficient, though there can be no doubt as to the biological and competitive advantage that is having deep rooting systems, as old vines do, in creating plants not just capable of surviving longer but also give much better wines in the process. Survival of the fittest in more ways than one, in other words. But clearly, there’s more to the equation, and another explanation of the superiority of wines made from old vines is the selection mechanism formed over time in viticulture—namely, the long-term effect of survivorship bias.

Vines are not passively retained over time. On the contrary, most vineyards undergo multiple rounds of active renewal. At different historical stages, vines with insufficient yields, unstable quality, or an inability to support prevailing economic models are often removed and replanted. Therefore, old vines that persist across several decades usually indicate that, through repeated assessments, they were deemed “worth keeping.” In this sense, old vines are a result of selection and not just a single causal facto of quality. This selection mechanism is often closely linked to economic considerations. In many regions focused on inexpensive or mid-priced wines, the low yields, high management costs, and difficulties with mechanization associated with old vines are not economically viable. As labor costs rise and markets demand stable yields, vineyard renewal is often regarded as a rational and necessary decision rather than a rejection of existing quality. The disappearance of many old vines is thus more often the result of economic non-viability than of failure in terms of quality. Whether that is the correct approach is open to debate, but it is the reality of the situation for many wineries.

For this reason, old vines that still exist today tend to be concentrated in environments capable of supporting quality-driven production systems: superior sites, clear stylistic positioning, and economic structures that allow low yields to coexist with high levels of input. Under such conditions, the potential advantages associated with old vines—such as structural stability, a more measured pace of development, and durability over time—are more likely to emerge. Once removed from these premises, however, vine age alone is insufficient to compensate for limitations in site or management. Or perhaps more accurately, they are not allowed to.

Therefore, the association between old vines and high quality does not stem only from age itself, but also from a system that has been repeatedly filtered by time. When placed in an appropriate context, old vines do not signify only a romanticized promise of quality, but rather a long-term balance that remains viable between quality, terroir, and economic reality.

The wines in this tasting