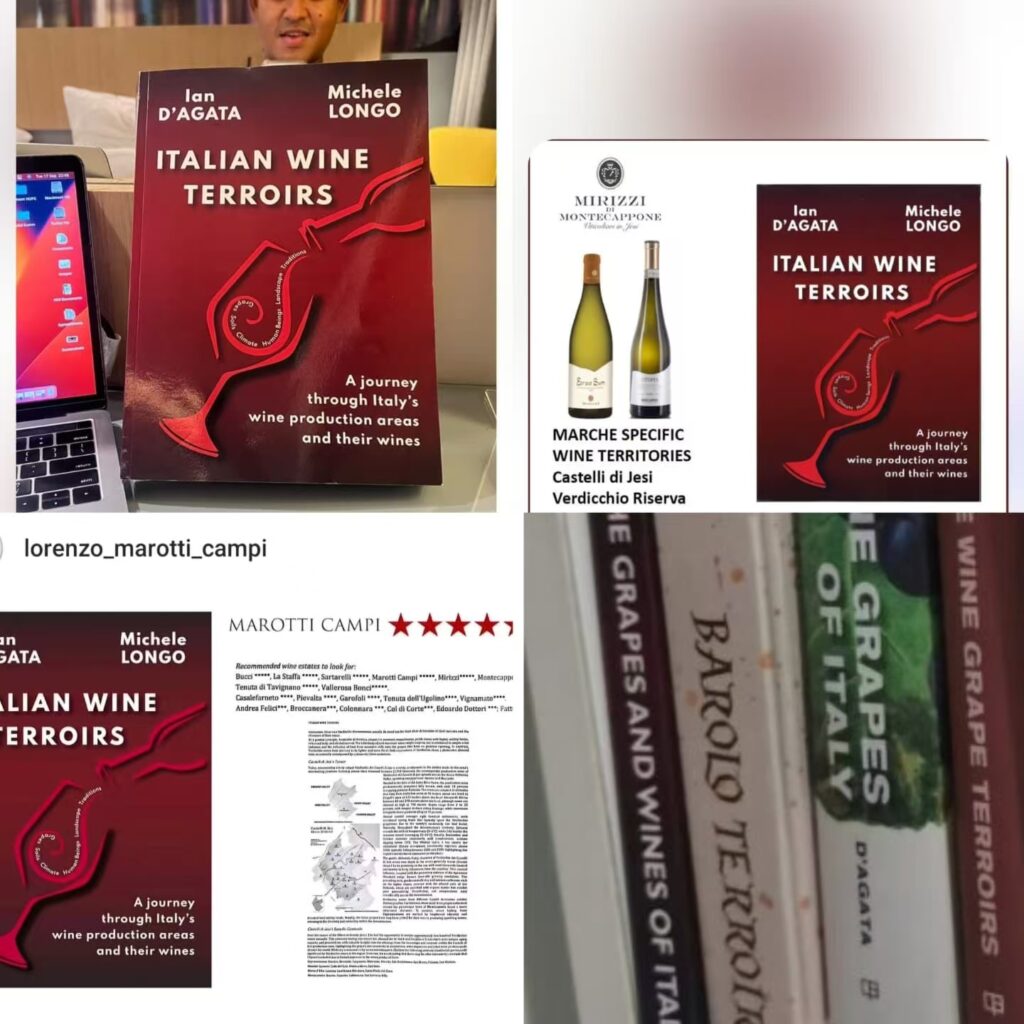

Italian Wine Terroirs is the brand-new wine book written by Ian D’Agata, together with long-time friend and colleague Michele Longo, and is available at www.amazon.com. It’s a an awe-inspiring, jaw-dropping doozy, already dubbed a “masterpiece” by Michelin star restaurant sommeliers, wine writing colleagues and wine producers.

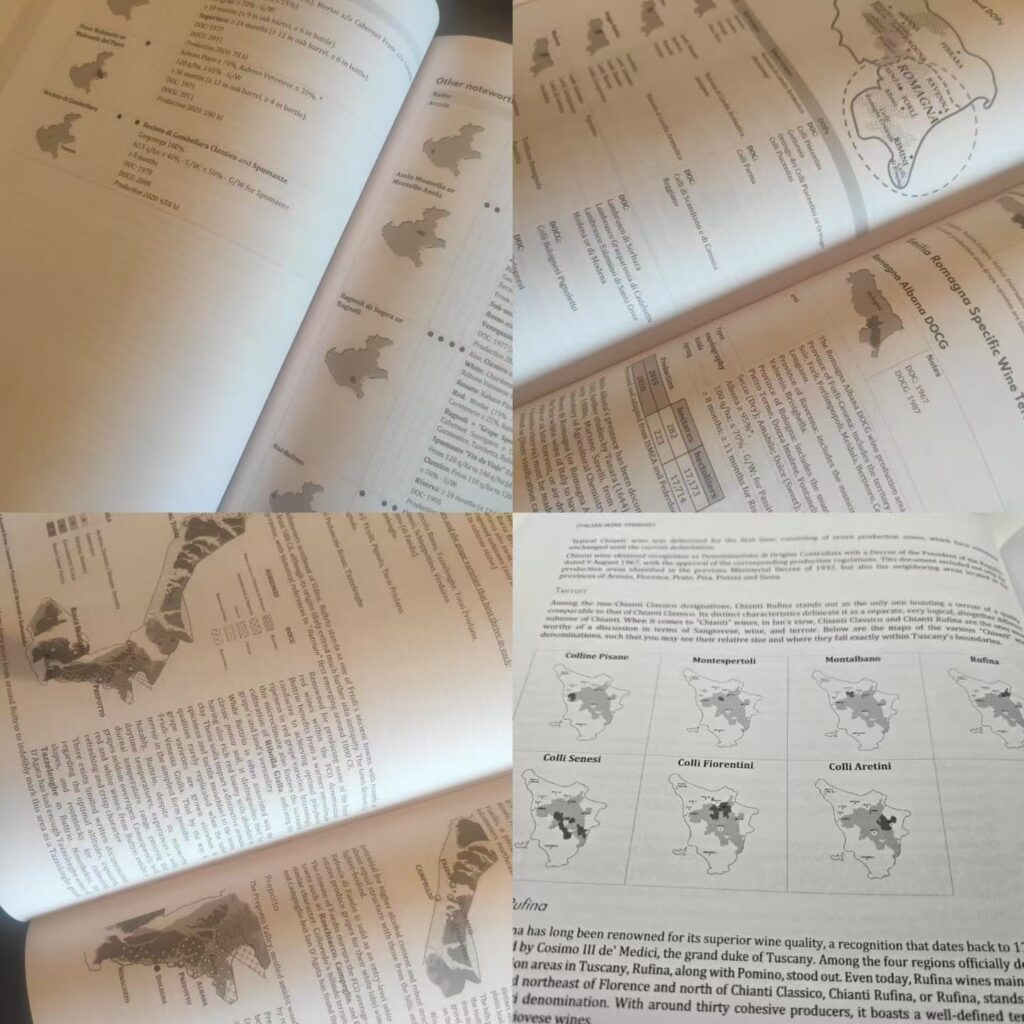

After having published two years ago their award-winning The Grapes and Wines of Italy: The Definitive Compendium Region by Region, D’Agata & Longo have followed up with another benchmark textbook on Italian wine that falls neatly within the same portfolio of easy to read paperback study guides on Italian wines, but that at the ame time are detailed enough to serve as reference texts on the subject too. For at over 450 pages long, and containing over 100 tables, graphs and maps, plus lists of the best estates to look for in each wine denomination (graded with one to five stars), that’s exactly what Italian Wine Terroirs is: a benchmark, true state of the art textbook on Italian wine that tells it like it really is.

In fact, the book’s subtitle, “A Journey Through Italy’s Wine Territories and Their Wines” could not be more apt in explaining what the book has in store for all its eager readers. World-famous wine denominations and territories such as those of Barbaresco, Barolo, Bolgheri, Brunello di Montalcino, Chianti Classico, Collio, Etna, Franciacorta and Valpolicella are dealt with extensively (some more so than others, in truth), but importantly, so are important wine areas of Italy that are internationally slightly less well-known in all their intricacies. For example, Aglianico del Vulture, Chianti Rufina, Fiano di Avellino, Friuli Carso, Friuli Isonzo, Greco di Tufo, Montepulciano d’Abruzzo, Taurasi, the Valle d’Isarco, the Val Venosta, Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi, and Verdicchio di Matelica are all broached extensively. Even more useful and interesting are all those sections of generally really unknown wine production areas (unknown outside of Italy, but even within Italy in-depth knowledge about them is relatively thin and doesn’t go that far…) such as Ischia, the Lipari Islands, Pantelleria, the Riviera Ligure di Levante and Ponente of Liguria, the Valle d’Aosta and many, many more.

The stated goal of the authors is to have wine lovers start thinking and speaking of Italian wines in the same way they think about and address the wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy, Napa and Sonoma, Mosel and Pfalz, Central Otago and Marlborough, Niagara and Prince Edward County and other wine production areas of the world. Wine lovers are well aware that Margaux and Pauillac both make Bordeaux wines: but at the same time, they are also very aware of the differences the wines of those two Bordeaux regions showcase in spades. They are Bordeaux wines, but also distinct Bordeaux wines. Similarly, wine lovers and wine professionals realize that the wines of Pommard differ strongly from those of Vosne-Romanée and Gevrey-Chambertin, even though they are all Burgundy wines. Even more pointedly, wine lovers and connoisseurs can discuss at length the different aspects of the wines from the Les Amoureuses and the Les Fesseulottes vineyards of Chambolle-Musigny, or of Charmes-Chambertin, Mazis-Chambertin and Chambertin itself. But hardly anyone can do when it comes to almost all Italian wines. “One of my goals in life has always been to elevate the level of discussion surrounding Italian wine, which is all too often reduced to pat phrases like “What a lovely Trebbiano wine” or “what a jolly good Malvasia”, but that way of referring to Italy’s wines is both inexact and demeaning” states Ian D’Agata matter-of-factly. “For one thing, Italy has at least seven different Trebbiano and eighteen different Malvasia varieties, all of which are mostly unrelated and all of which give different wines, to greater or lesser degrees; furthermore, taking Malvasia Istriana grapevines as an example, in Friuli’s Carso, Malvasia Istriana will give noticeably different wines than those made with it when it is planted in Friuli’s Isonzo or Colli Orientali, much as Pinot Noir does when planted in Central Otago and in Martinborough, never mind Volnay and Pommard. With this book, we hope to have people slowly start thinking and talking about Italian wines in slightly different terms than they do now. And before you ask, yes, I am the first to realize it will be a very slow and at times painful process. But this book is undoubtedly a step in the right direction in ensuring that this will happen one day”. Michele Longo echoes much the same thoughts: “Listen, we aren’t doing anything voodoo or esoteric here. After all, we have gotten to the stage in generalized wine knowledge where most wine professionals and super-dedicated wine lovers are well aware that a Barolo from Verduno is very different from one made with grapes grown in Monforte or Serralunga d’Alba. It’s much the same with most other Italian wines: therefore, with Italian Wine Terroirs we aim to help wine lovers everywhere start to gain an understanding about those other wines too, and by that I mean with respect to their different communes and terroirs”.

There is literally nothing quite like Italian Wine Terroirs available on Italian wine, save for D’Agata’s own Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs (INWGT, published by University of California Press). As great (and frankly, very complex) as that book was, it described a much smaller number of Italy’s wine denominations and terroirs, while also being limited to native grape only. Italian Wine Terroirs does not broach specific wine terroirs with quite the same degree of information as did INWGT, but it does broach all of Italy’s wine denominations, independently of whether they are planted mostly to international or native grapes, or both. Honesty dictates I make clear that the level of detail Italian Wine Terroirs offers in describing more or less all of Italy’s wine production areas (including their history, geology, and climate), as well as their wines, is absolutely unmatched by any other wine book on Italian wines available today. In fact, the book’s two Forewords and the Introduction, right at the beginning of Italian Wine Terroirs, are three of the most entertaining things I have ever read on wine (never mind Italian wine: I mean wine, period) and are worth the price of the book alone, and that’s not even counting all the rest the book has to offer (which is plenty). But then you would not expect any different with a book written by Ian D’Agata, universally considered as the most credible and knowledgeable wine writer on Italian wine today.

In contrast to other books written by individuals who don’t even live in the country the wines of which they are writing about (or have lived there only briefly), Italian Wine Terroirs is the result of decades of on the field investigations, research and interviews conducted both by Michele Longo, an Italian who lives in Turin and visits Italian wineries regularly, and Ian D’Agata who lived, at different times, over thirty years in Italy and visited wineries with even more assiduity and regularity than Longo. They are two of Italy’s most respected and well-liked wine writers (importantly, by winery owners and winery staff too) and so it follows that the end-result could not have been anything but the way Italian Wine Terroirs has turned out to be.

Printed in an easy-to-read format, this paperback will prove to be the ideal study guide for anybody enrolled in wine courses and classes at the beginner, intermediate and highest levels, or for those who simply enjoy wine and have always wished to know and understand more about Italy’s wines, a fascinating but (almost) hopelessly confusing affair.

And from my perspective, perhaps best of all about the book is that, as is always the case with D’Agata’s and Longo’s books, Italian Wine Terroirs has not been paid for in any part by Italian producer associations, consortiums, government agencies, individual producers or any other entity. You will therefore not have to suffer through reading shananigans about “emerging wine areas” or “greatly improved wines”, that are all too often anything but.

In ultimate analysis, D’Agata & Longo’s Italian Wine Terroirs is a labour of love, clearly written with passion and a deep love for their subject matter. It offers a frank, candid, and extremely detailed assessment of the Italian wine scene and its wines, which, much as the country itself, can best be described as the realm of (more or less) “organized chaos”. But one that you will greatly enjoy, just like Italian Wine Terroirs.